Historically, maintenance has been viewed as a necessary evil that, while valuable, costs the company money. Although some organizations may still hold this idea to be true, many companies today regard maintenance as an essential part of business operations that has an impact on the bottom line. What accounts for the change in thinking? To find our answer, let’s take a quick look at the history of maintenance.

The First Industrial Revolution

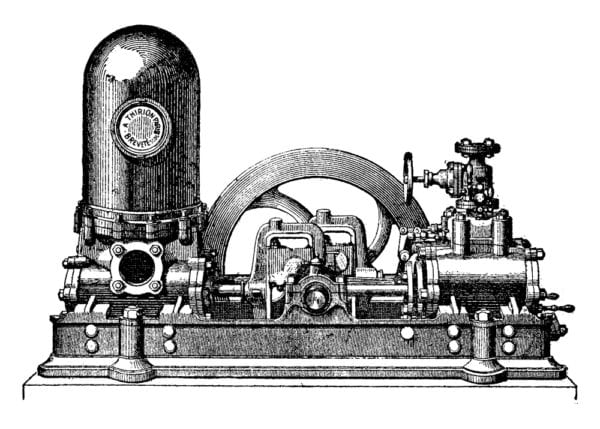

Near the end of the 18th century, the first Industrial Revolution was just beginning to take shape in the United Kingdom and across Europe, and later made its way to the United States. Steam power started being used for production, and machines were gradually replacing human labor in manufacturing and agriculture.

Overall, the machinery of the time was tough, had basic controls, and was fairly reliable. Also, production demands were not as great as they are today, so avoiding downtime was not a critical concern. Factories employed a “use it until it breaks” mentality and focused largely on corrective maintenance, which was performed primarily by machine operators. Machines that could not be fixed were replaced.

The Second Industrial Revolution

The Second Industrial Revolution started in the United States during the mid-to-late 19th century. During this period, new discoveries and innovations drove manufacturing forward. The discovery of electricity meant that factories could stay open longer and electricity-driven machines could produce products at a much larger scale.

Factories continued to replace people with machines, and Henry Ford’s assembly line further strengthened mass production. Maintenance teams became slightly more proactive and used a basic time-based maintenance (TBM) strategy which involved replacing parts at specific time intervals, whether it was needed or not.

Once the Great Depression hit in the early 20th century, little money was available to replace machines. Maintenance became a more specialized skill set as employees learned how to fix and repair what was broken. At the same time, machine operators were directed to push equipment to its limits, resulting in frequent failures and high maintenance costs. Unfortunately, rising costs were typically blamed on the maintenance team.

War Production and World War II

In 1939, conflict was spreading throughout Europe and Asia, setting the stage for World War II. Factories in the United States were being converted from producing consumer goods to producing war materials to support Great Britain and other American allies.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt set aggressive goals to out-produce and overwhelm the Axis Powers. As millions of Americans entered the military, their positions in the workforce were taken by millions of women, minorities, and other citizens.

Besides becoming combat pilots, many women started working for military support services, including aircraft maintenance. As the needs to maintain and fix military vehicles and manufacturing equipment became a priority, maintenance started to become an independent function.

The United States Department of War even recruited skilled mechanics and technicians from machine manufacturers, such as John Deere, to serve as a military maintenance units that kept combat equipment in working order.

Aftermath of World War II

Following World War II, war production converted back to domestic goods as soldiers returned home from the battlefields. The strong, post-war economy kicked off the baby boom in the United States, and thriving markets became more competitive. To stay ahead of their rivals, manufacturers sought to increase their production which meant that maintenance costs would also grow if nothing changed. In response, factories began to put more effort into preventive maintenance activities.

Meanwhile, the industrial rebuilding of Japan gave birth to the concept of total productive maintenance (TPM), where small groups of workers were responsible for performing routine maintenance on their own machines to keep the equipment in top operating order.

In the 1960’s, high airplane crash rates caused the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and United Airlines to investigate the effectiveness of preventive maintenance practices in the airline industry. This investigation debunked long-held beliefs that assets and components had a set “lifetime” before they had to be replaced. Under what was called reliability-centered maintenance (RCM), more focus was placed on understanding and prioritizing asset failure and developing plans to better manage those failures. RCM concepts were soon adopted by other asset-intensive industries and large corporations that required maximum uptime.

The Third Industrial Revolution

The rise of electronics in the second half of the 20th century launched a new era of industrial automation. Production processes became more automated thanks to programmable logic controllers (PLCs) and robots. Employee safety became a maintenance concern as highly-performing equipment brought about more risk for accidents. Punch card-based computerized maintenance management systems (CMMS) were used in large companies to remind technicians to perform simple maintenance tasks. Later, technicians fill out paper forms, which were then handed to data-entry clerks to type into mainframe computers to track maintenance work for each asset.

Building on the concepts of RCM, maintenance strategies in the 1990’s began using the concept of risk when making maintenance decisions. Risk-based maintenance (RBM) sought to optimize maintenance resources by prioritizing the risk of failure, with high-risk assets being subject to more intensive maintenance programs.

The early ‘90’s also saw the expansion of personal computing, which made CMMS solutions more affordable for medium-sized companies. Microsoft Access® and Excel®-based maintenance management became common. Although many companies still rely on these systems, there are more powerful options available today.

Into the 2000’s

Advancements in computing and information technologies into the 2000’s further impacted the way maintenance was performed and managed. CMMS systems could now be hosted on the cloud and accessed over the internet.

Low-cost, Software as a Service (SaaS) subscriptions and minimal IT requirements made cloud-based CMMS attractive to, and more affordable for, small businesses. Improved wireless and mobile technology made it possible for organizations to access their CMMS from internet-connected smart phones, tablets, and laptop computers.

The continued growth and application of internet technologies in recent years allows world-class organizations to implement advanced maintenance strategies such as condition-based maintenance (CbM) and predictive maintenance (PdM). With these strategies, internet-connected sensors are used to monitor asset conditions such as vibration, temperature, noise, and pressure, and predict when failure is about to occur. CMMS software continues to be improved to support these advanced maintenance strategies.

Keep Up with Changing Maintenance Practices with FTMaintenance

The history of maintenance evolved drastically over times and continues to change today. No matter what maintenance strategies you use, it is important to have a system in place to help you manage maintenance activities and provide value to your organization.

FTMaintenance is a feature-rich, easy-to-use platform that allows you to easily document, manage, and track maintenance activities. With a full suite of tools for managing work orders, assets, inventory, preventive maintenance, and more, FTMaintenance CMMS software will help you improve your current maintenance operations and prepare for the road ahead. Request a demo to see FTMaintenance in action!