Key Takeaways

- Availability and reliability are related, though different metrics used to measure asset performance

- Availability measures the amount of time assets spend in production vs. being out for repair

- Reliability measures how frequently assets fail

- Computerized maintenance management system (CMMS) software, like FTMaintenance, tracks asset performance data used to calculate availability and reliability

Two meaningful metrics used to evaluate asset performance are availability and reliability. Though often used interchangeably, both terms have specific meaning in a manufacturing maintenance context. For the maintenance team, understanding the difference between availability and reliability ensures that maintenance activities effectively target issues affecting plant performance.

This article discusses the differences between availability and reliability, their relationship to one another, and how maintenance can address each.

What is Asset Availability?

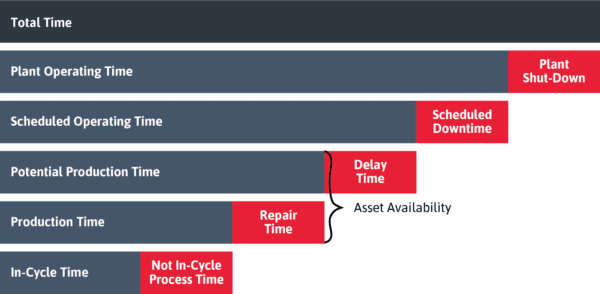

We acknowledge that organizations define and calculate availability in various ways, depending on their process and performance goals. This discussion focuses on availability as it relates to production and examines equipment-related factors that impact availability, such as malfunctions and repairs.

According to The Association for Manufacturing Technology (AMT), asset availability is “the percentage of potential production time during which equipment is operable, that is, operation is not prevented by equipment malfunction.” Put another way, asset availability measures the amount of time equipment was running and producing goods compared to the time production was stopped due to repairs.

Calculating Asset Availability

Refer to the chart in the previous section. As shown, asset availability considers three factors:

- Potential Production Time: the amount of time equipment was expected to run, not counting non-equipment-related delays

- Production Time: the amount of time equipment actually ran

- Repair Time: the amount of time equipment was not running due to an unexpected malfunction and its subsequent repair

![]()

To calculate asset availability, divide production time by the potential production time, then multiply the result by 100 to express the value as a percentage.

Let’s look at an example: A production asset ran for 150 hours in a month, but experienced 20 hours of downtime due to a breakdown and waiting for parts. Therefore, out of 170 hours of potential production, actual production time was 150 hours.

Availability = (150 hours ÷ 170 hours) × 100

Availability = 0.88 × 100

Availability = 88%

Another way to think of asset availability is in terms of uptime and downtime. Uptime is generally defined as the time equipment is running; downtime is time equipment is broken down and/or being repaired. Potential production time, then, is considered the sum of uptime and downtime. The asset availability formula using uptime and downtime then becomes:

![]()

Further, uptime can be measured using the Mean Time Between Failure (MTBF) metric, which calculates the average amount of time equipment runs before failing. Downtime can be measured using the Mean Time to Repair (MTTR) metric, which calculates the average amount of time it takes to make a repair. Therefore, a third way to calculate asset availability is to use the following formula:

![]()

However, since MTBF and MTTR are averages, calculating availability using this formula may be less precise than others. Read more about MTBF and MTTR in our article, 3 Important Asset Management KPIs and How to Use Them.

How Maintenance Can Improve Asset Availability

Availability is a performance metric traditionally tracked by production, not maintenance. However, maintenance teams impact availability because they are responsible for finding ways to minimize unplanned downtime and increase the speed of equipment repairs when failures occur.

To do so, organizations can equip maintenance technicians with the information and tools needed for effective troubleshooting. For example, work order history, failure tracking data, and owner’s manuals help technicians to quickly diagnose failures and develop solutions. In addition, indirect factors such as organized stockrooms, appropriate inventory levels, and effective labor utilization indirectly leads to more efficient maintenance.

Advanced organizations may also perform root cause analysis (RCA) and leverage failure codes to track equipment failures. RCA helps identify probable causes of breakdowns and provides data from which to build or tweak preventive maintenance strategies. Comprehensive failure tracking allows maintenance technicians to quickly troubleshoot issues, thereby reducing repair time.

Asset availability can also be improved by implementing a proactive maintenance strategy. Proactive, as opposed to reactive, maintenance lessens the likelihood of unplanned downtime events all together, thereby improving asset availability.

What is Asset Reliability?

Asset reliability, according to AMT, is “the probability that machinery and equipment can perform continuously for a specified interval of time without failure, when operating under stated conditions.” While availability measures whether equipment was operable or not, reliability measures the frequency of failures.

Calculating Asset Reliability

Reliability can be calculated in multiple ways, using either Mean Time Between Failure (MTBF) or failure rate.

Using Mean Time Between Failure (MTBF)

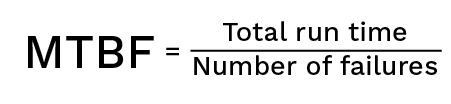

The Mean Time Between Failures (MTBF) metric is the most often used measure of asset reliability. It measures how long assets run, on average, before experiencing a malfunction.

To calculate MTBF, divide the total time the asset was running by the number of failures it experienced during that time period. For example, a machine that ran for 3000 hours and experienced 5 failures has a MTBF of 600 hours.

MTBF = 3000 hours ÷ 5 failures = 600 hours/failure

Stated another way, the maintenance team can expect an equipment failure approximately every 600 hours.

Using Failure Rate

![]()

Another way to calculate reliability is to use the failure rate, which is the frequency at which an asset fails. To calculate failure rate, divide the number of failures by the total run time. Note that failure rate is the inverse of Mean Time Between Failure, and can be calculated by dividing 1 by the MTBF.

Let’s calculate failure rate using the same values as before:

Method 1: Using Run Time

Failure Rate = 5 failures ÷ 3000 hours = 0.0016 failures/hour

Method 2: Using MTBF

Failure Rate = 1 ÷ MTBF

Failure Rate = 1 ÷ 600 hours/failure = 0.0016 failures/hour

Because this value is so small, it is easier to think of reliability in more useful measures of time, such as years. Translate the hourly failure rate into a yearly rate by multiplying the failure rate by 8,760, the number of hours in a year. Therefore:

Failure Rate (per year) = 0.0016 failures/hour × 8,760 hours/year = 14 failures/year

How Maintenance Can Improve Asset Reliability

Improving reliability boils down to minimizing the frequency of unplanned downtime events. Organizations use a range of maintenance techniques to reduce the frequency of unplanned downtime including:

- Planned corrective maintenance (CM)

- Preventive maintenance (PM)

- Condition-based maintenance (CbM)

- Predictive maintenance (PdM)

The goal of these types of maintenance is to lessen the likelihood of failure by proactively servicing equipment. However, each asset has different needs depending on its age, condition, usage, and known failure conditions.

Maintenance teams must use an appropriate combination of maintenance activities to optimize the asset’s performance. Establishing this maintenance mix is one of the foundations of a higher-level maintenance strategy called reliability-centered maintenance (RCM).

Availability vs. Reliability

To briefly recap:

- Asset availability measures the amount of time equipment was in an operable state vs. being repaired.

- Asset reliability measures how long equipment performs its intended function (i.e., how often it breaks down).

So what is the relationship between the two metrics? Generally speaking, assets that are more reliable are also more available. Intuitively, it makes sense – the less equipment breaks down, the longer it can be used for production. However, this is not always the case.

Equipment has high reliability and low availability when repair times are long. For example, a machine component fails, causing a major breakdown. There is no obvious cause of the malfunction and it has not happened in the past. The maintenance team must investigate the problem, determine and test a solution, and possibly wait for parts to arrive. Though only one failure occurred within the time period (high reliability), it takes a long time to repair the asset due to its complexity (low availability).

Now let’s look at the opposite scenario. Equipment has high availability but low reliability when there are multiple failures, but each can be resolved quickly. For example, a machine is stopped multiple times for minor corrective maintenance that takes a few minutes to complete in each instance. While, the total repair time is low (high availability) failures are high (low reliability), which is undesirable.

Asset Management Software

One of the most effective ways to improve asset availability and reliability is to implement a computerized maintenance management system (CMMS). CMMS software centralizes critical asset data, helping maintenance teams quickly identify common maintenance issues, troubleshoot failures, and access important maintenance documentation. The system also allows managers to create customized maintenance plans for each asset.

As a data analysis tool, CMMS maintenance management reports help organizations gain valuable insights into asset performance and maintenance operations. In terms of availability, a CMMS can be used to provide accurate repair time data to the production team, helping them identify other causes of stopped or slowed production. For reliability calculations, a CMMS helps organizations track important asset management KPIs including MTBF.

In addition, CMMS reports can be used to better understand equipment life expectancy, assess the effectiveness of maintenance activities, and set improvement goals.

Improve Asset Performance with FTMaintenance Select

Asset management is a key component of maintenance management. FTMaintenance Select is CMMS software that can be used to measure and track data used to calculate asset availability and reliability. Schedule a demo today to learn more about how FTMaintenance Select makes maintenance management easy.

Recent Comments