Key Takeaways

- Proper work order management allows you to efficiently process and complete work orders

- The work order management process covers the entire work order lifecycle, from initial request to closure and analysis

- Computerized maintenance management system (CMMS) software, like FTMaintenance, simplifies and automates work order management

What is Work Order Management?

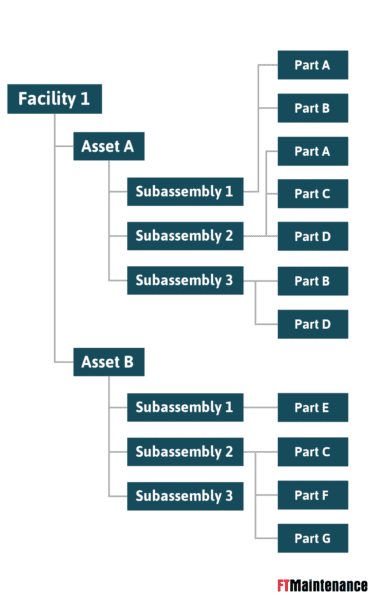

Work order management is the systematic approach of processing and completing maintenance work orders in a timely manner in order to minimize asset downtime. Work order completion depends on the availability of other maintenance resources such as assets, parts, people, and money.

Importance of Work Order Management

Traditionally, maintenance teams have relied on paper-based work orders to communicate job assignments. Though the work orders themselves may be easy to create by hand, the management of paper-based work orders is labor-intensive and often introduces more problems than it solves.

For example, maintenance staff must interpret bad handwriting, leading to incorrect documentation. Physical copies are liable to get misplaced and lost, resulting in missed maintenance. Stacks of paper clutter up file cabinets and desks, making it difficult to find historical work orders.

Some maintenance teams have advanced to spreadsheet-based work order management, but these systems carry their own limitations. Spreadsheets can only be modified by one person at a time, making it difficult for technicians to see the most up-to-date information. Work orders generated by spreadsheet software must still be printed, bringing along the challenges discussed earlier. Using spreadsheet software may be daunting for staff.

As organizations grow, “old-school” work order management methods quickly become unsustainable and inefficient. Even more so, a renewed focus on operational efficiency has put a spotlight on the functions of the maintenance department. To improve work order management, organizations invest in a computerized maintenance management system (CMMS).

Work Order Management Process

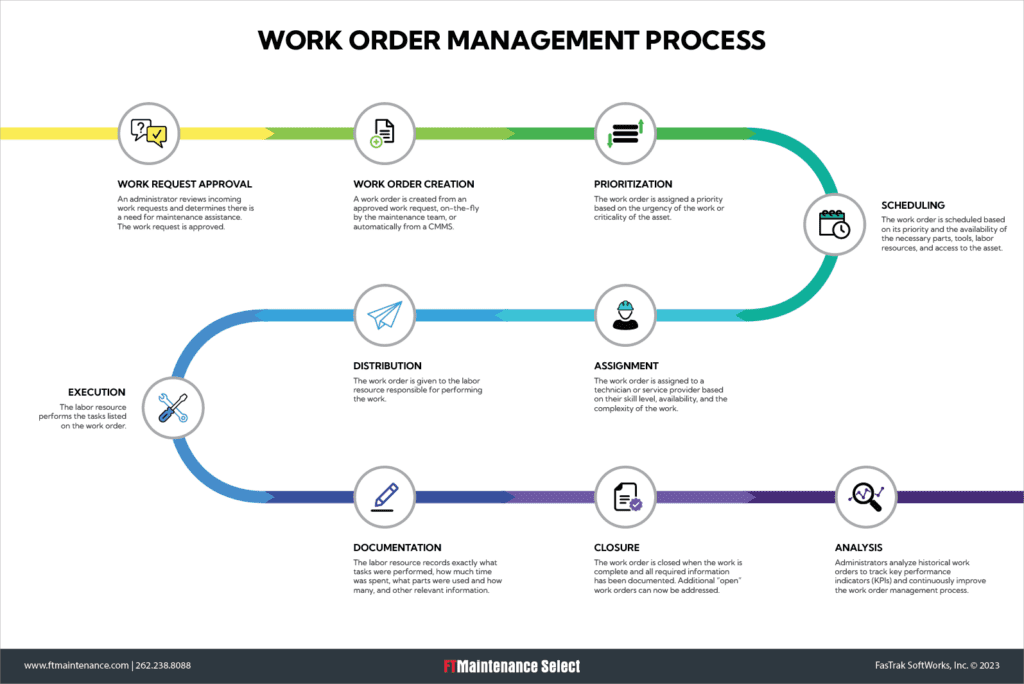

Proper work order management considers the work order at every stage of its life from request to completion. The following sections describe what happens in each step of the work order management process. You will notice how a CMMS makes the work order management process more streamlined and efficient.

Work Request Approval

The need for maintenance work is often communicated through a work request or service request. An approver will review the request and determine whether a legitimate need exists, if enough information is available to create a work order, or if the issue has already been reported. Many organizations use the maintenance request feature of a CMMS to handle incoming requests. If the request is valid, it will be approved and a work order will be created.

Read also: What is a Maintenance Request System?

Work Order Creation

The creation of a work order signifies that authorization has been given to perform the requested work. Work orders are created from approved maintenance requests, by the maintenance staff, or automatically from a CMMS. Using a mobile CMMS, technicians can create work orders from the field.

Prioritization

Prioritizing work orders involves determining which work orders are to be completed first. A work order’s priority is typically determined by the criticality of the job or asset. For example, work orders related to safety (of sites or staff) may be given a high priority. Lower priority work orders include routine preventive maintenance or non-essential maintenance requests.

The maintenance team creates standards for what makes a work order high or low priority. Not only will this allow the truly high priority work orders to be completed faster, but when a backlog does occurs, it should consist of low-priority work.

Scheduling

The scheduling of work orders is based on their priority. Emergency work orders are addressed without delay. Preventive maintenance work orders are typically scheduled based on calendar- or runtime-based intervals, or by the asset manufacturer’s maintenance guidelines. However, timing is not the only consideration when scheduling work orders.

Maintenance managers consider the availability of technicians, spare parts and supplies, and tools or other special equipment needed to complete work orders. CMMS software allows you to visualize the maintenance workload and identify how staff can be used most effectively.

Assignment

Every maintenance team is made up of technicians with varying skills and abilities. Work orders should be assigned to the technicians best suited for the job. For larger organizations, technicians may specialize in a particular craft or have training on specific assets.

Small to medium-sized businesses are more likely to use jacks-of-all-trades who can perform a multitude of maintenance tasks. Determining who is best for the job may be done by first-hand experience, but can also be identified using maintenance reports from a CMMS.

Distribution

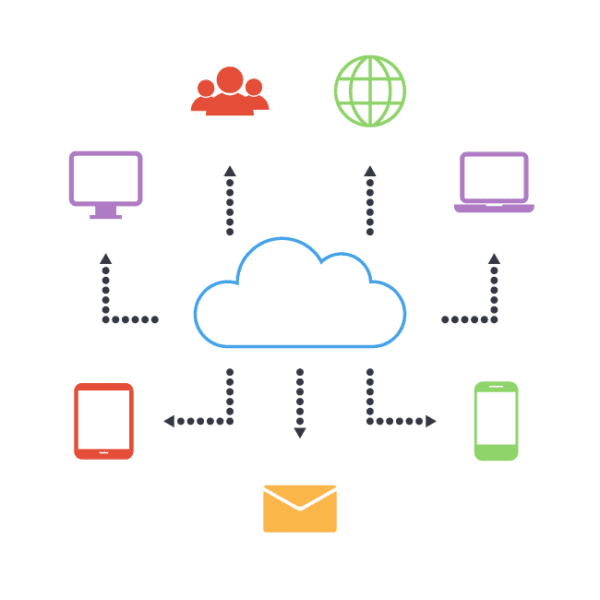

Once work orders are scheduled and assigned, they must find their way into the hands of technicians. Work orders can be physically handed out, but it takes time to track down technicians. CMMS software features automatic printing to designated printers and automatic emailing to staff. A CMMS with mobile capabilities allows technicians to instantly receive work orders on internet-connected devices.

Execution

Execution is the act of the assigned technician(s) performing the tasks listed on the work order. A CMMS allows you to track the progress of work orders in real-time so that you can ensure technicians are staying on top of their work.

Documentation

Part of the work order management process is training workers to document all results, both the good and bad. The more accurate information you have, the better off you will be. Technicians should take care to record exactly what was done, how much time was spent, what parts were used, and so on.

Documenting work in a CMMS leads to more accurate maintenance records that can be used to identify areas of improvement and assist in future troubleshooting. Poor documentation leads to inaccurate or flawed reports – as they say, “garbage in, garbage out.” The better your work order documentation, the better you will be able to monitor and track key performance indicators (KPIs) using CMMS maintenance reports.

Closure

Work order closure occurs when all tasks have been performed, all services delivered, and the job is complete. Technicians are now available to begin working on other “open” work orders.

Analysis

Your collective work order history is the foundation for meaningful reporting. Without the reporting functionality of a CMMS, it becomes very difficult to track key performance indicators (KPIs) that provide glimpses into your process. For example, how easily can you calculate the number of work orders that were created or closed using a spreadsheet or paper-based tracking system?

Improve Work Order Management with FTMaintenance

Even the best work orders can fail without a solid system to manage them. FTMaintenance is powerful work order software that simplifies your work order management process. Featuring automated work order creation, assignment, distribution, and closure, FTMaintenance reduces the amount of administrative work involved in accomplishing your every day maintenance activities. Request a demo to see how FTMaintenance can improve your organization’s work order management process.

Recent Comments