Key Takeaways

- Proper work order management allows you to efficiently process and complete work orders

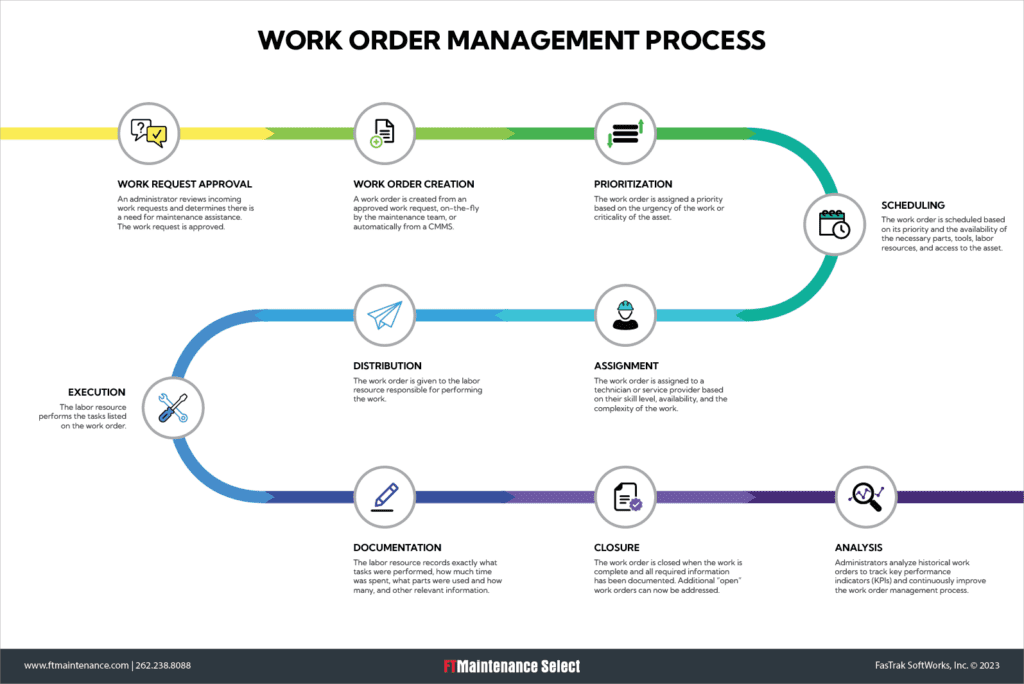

- The work order management process covers the entire work order lifecycle, from initial request to closure and analysis

- Computerized maintenance management system (CMMS) software, like FTMaintenance, simplifies and automates work order management

Work order management is critical to maintaining asset reliability and minimizing downtime. However, managing work orders is more than tracking tasks – it’s a process that involves multiple interdependent steps that must be carefully coordinated. In this article, we break down the key stages of the work order management process and explain how maintenance software improves efficiency by automating routine tasks, tracking completion, and reducing manual work.

What is Work Order Management?

Work order management is the systematic approach of processing and completing maintenance work orders in a timely manner in order to minimize asset downtime. The process involves many steps and also depends on the availability of other maintenance resources such as assets, parts, people, and money. Once work orders are closed, they are analyzed to help improve work order schedules, work quality, and streamline the process.

Why is Work Order Management Important?

Traditionally, maintenance teams rely on paper-based systems to communicate job assignments. Though the work orders themselves may be easy to create by hand, manually managing them is labor-intensive and often introduces more problems than it solves.

For example, maintenance staff must interpret bad handwriting, leading to incorrect documentation. Physical copies are liable to get misplaced and lost, resulting in missed maintenance. Stacks of paper clutter up file cabinets and desks, making it difficult to find historical work orders.

Some maintenance teams have advanced to spreadsheet-based work order management, but these systems carry their own limitations. Spreadsheets can only be modified by one person at a time, making it difficult for technicians to see the most up-to-date information. Work orders generated by spreadsheet software must still be printed, bringing along the challenges discussed earlier. In addition, using spreadsheet software may be daunting for employees who prefer hands-on tasks over screen-based work.

As organizations grow, “old-school” work order management methods quickly become unsustainable and inefficient. Even more so, a renewed focus on operational efficiency has put a spotlight on the functions of the maintenance department. To improve work order management, organizations invest in a computerized maintenance management system (CMMS).

Work Order Management Process

Proper work order management accounts for every stage in a work order’s lifecycle, from initial request to completion. The following sections describe what happens in each step of a typical work order management process. Along the way, notice how a CMMS makes the work order management process more streamlined and efficient.

Work Request Approval

The need for maintenance work is often communicated through a work request or service request. An approver will review the request and determine whether a legitimate need exists, if enough information is available to create a work order, or if the issue has already been reported. Many organizations use the maintenance request feature of a CMMS to handle incoming requests. If the request is valid, it will be approved and a work order will be created.

Read also: What is a Maintenance Request System?

Work Order Creation

The creation of a work order signifies that authorization has been given to perform the requested work. Work orders are created from approved maintenance requests, by the maintenance staff, or automatically from a CMMS. Using a mobile CMMS, technicians can create work orders from the field.

Prioritization

Prioritizing work orders involves determining which work orders are to be completed first. A work order’s priority is typically determined by the criticality of the job or asset. For example, work orders related to safety (of sites or staff) may be given a high priority. Lower priority work orders include routine preventive maintenance or non-essential maintenance requests.

The maintenance team creates standards for what makes a work order high or low priority. Not only will this allow the truly high priority work orders to be completed faster, but when a backlog does occurs, it should consist of low-priority work.

Scheduling

The scheduling of work orders is based on their priority. Emergency work orders are addressed without delay. Preventive maintenance work orders are typically scheduled based on calendar- or runtime-based intervals, or by the asset manufacturer’s maintenance guidelines.

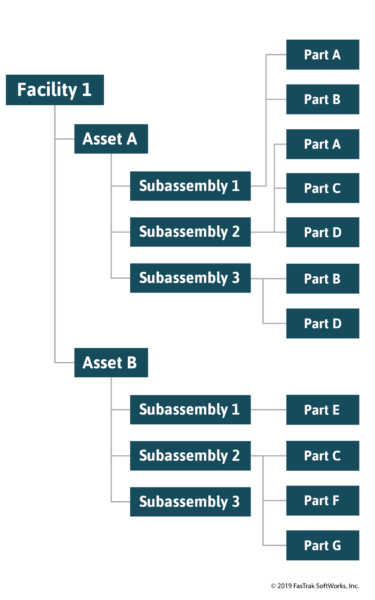

While timing plays a key role in work order scheduling, it’s not the only consideration. Maintenance managers must also account for the availability of technicians, spare parts and supplies, tools, and other special equipment needed to complete the job. CMMS software allows you to visualize the maintenance workload and identify how staff can be used most effectively.

Assignment

Every maintenance team is made up of technicians with varying skills and abilities. Work orders should be assigned to the technicians best suited for the job. For larger organizations, technicians may specialize in a particular craft or have training on specific assets.

Small to medium-sized businesses are more likely to use jacks-of-all-trades who can perform a multitude of maintenance tasks. Determining who is best for the job may be done by first-hand experience, but can also be identified using maintenance reports from a CMMS.

Distribution

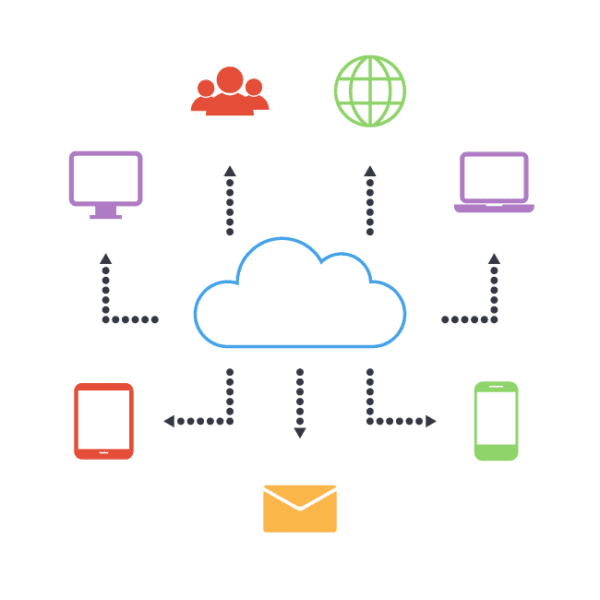

Once work orders are scheduled and assigned, they must find their way into the hands of technicians. Work orders can be physically handed out, but it takes time to track down technicians. CMMS software features automatic printing to designated printers and automatic emailing to staff. A CMMS with mobile capabilities allows technicians to instantly receive work orders on internet-connected devices.

Execution

Execution is the act of the assigned technician(s) performing the tasks listed on the work order. A CMMS allows you to track the progress of work orders in real-time so that you can ensure technicians are staying on top of their work.

Documentation

An important aspect of work order management is ensuring that technicians accurately document all results—whether successful or not. The more accurate information you have, the better off you will be. Technicians should take care to record exactly what was done, how much time was spent, what parts were used, and so on. CMMS allows for easy documentation, which leads to more accurate maintenance records that can be used to identify areas of improvement and assist in future troubleshooting.

Poor documentation leads to inaccurate or flawed reports – as they say, “garbage in, garbage out.” Detailed work order documentation enables more accurate KPIs and insights from your CMMS reports.

Closure

Work order closure occurs when all tasks have been performed, all services delivered, and the job is complete. Technicians are now available to begin working on other “open” work orders.

Analysis

While the core of work order management focuses on day-to-day processing of work orders, organizations committed to continuous improvement should also track performance metrics to enhance their overall work order and maintenance management practices. Common work order management KPIs include:

- Maintenance Backlog: The number of hours it takes to complete pending work orders with your available resources

- On-Time Work Order Performance: The percentage of work orders completed by their due date

- Average Response Time: The amount of time it takes to start executing a work order after it has been created, most commonly used in organizations with a formal service request process

Tracking these KPIs brings better visibility to the efficiency of your work order management process, providing valuable insight into your performance and areas of improvement.

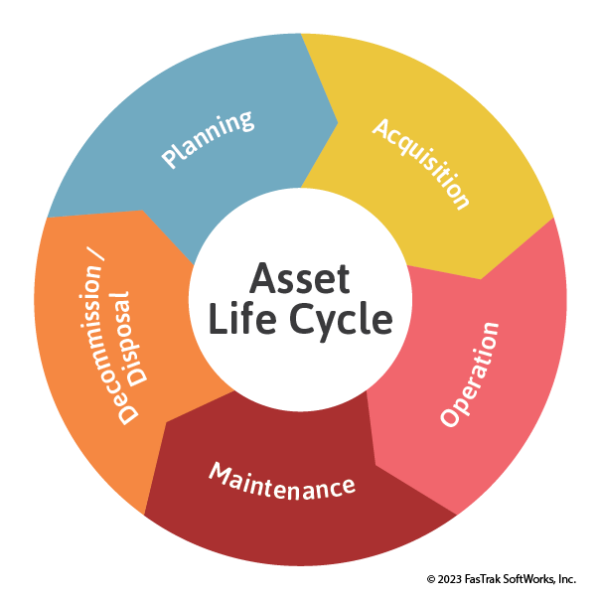

Aside from these KPIs, historical work orders also provide insight into asset health. Analyzing an asset’s service history helps identify recurring issues, failure patterns, and performance trends, revealing where adjustments to the maintenance strategy may be needed. These insights support more informed decisions about preventive maintenance frequency, repair versus replace strategies, and long-term asset planning.

Work Order Management Software

With so many steps involved in managing work orders, it’s no surprise that the process can quickly become overwhelming without the right tools. Work order management software, such as a computerized maintenance management system (CMMS), automates tasks at each stage, helping you efficiently track maintenance work orders throughout their entire lifecycle.

Modern work order management software allows maintenance teams to:

- Receive service requests from non-maintenance personnel via a dedicated request portal

- Automatically create work orders based on preset schedules or on demand

- Prioritize work orders based on maintenance type, asset, customer, or nature of the work

- Assign tasks to the right labor resource based on skills or availability

- Schedule preventive maintenance at regular intervals

- Track progress in real time

- Document what work was completed, when, and by whom

- Analyze work order history to identify trends and recurring issues that impact equipment reliability

- Report on work order performance to find opportunities to continuously improve

By using work order management software, organizations gain greater visibility into their maintenance operations and improve the consistency, accuracy, and efficiency of their work order processes.

Improve Work Order Management with FTMaintenance Select

Even the most well-planned maintenance efforts can fall short without an efficient work order management system. FTMaintenance Select simplifies every stage of work order management to help your team stay organized, reduce manual tasks, and respond to maintenance needs faster. Request a demo today to see how FTMaintenance Select puts you in control over your work order process.

Recent Comments