Effective asset management helps organizations maximize the value they get from physical assets. Although the discipline generally covers the entire asset lifecycle, in maintenance operations it focuses on maintaining equipment reliability, minimizing downtime, and controlling maintenance costs. In this article, we explore the asset management practices that maintenance teams use to improve availability and performance while supporting broader asset management goals.

What is Asset Management?

According to the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) standard 55000, asset management is “coordinated activity of an organization to realize value from assets.” In practice, this means managing physical assets in a way that aligns with organizational goals, balances costs, mitigates risks, optimizes performance, and delivers great value throughout the asset’s lifecycle.

Put simply, asset management means working together – across departments and systems – to get the most value out of equipment, facilities, and other assets. Value includes not only financial return but also reliability, safety, compliance, and operational performance.

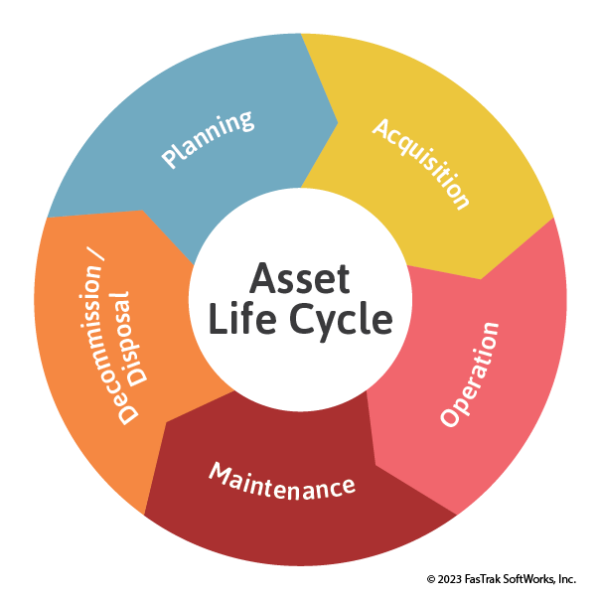

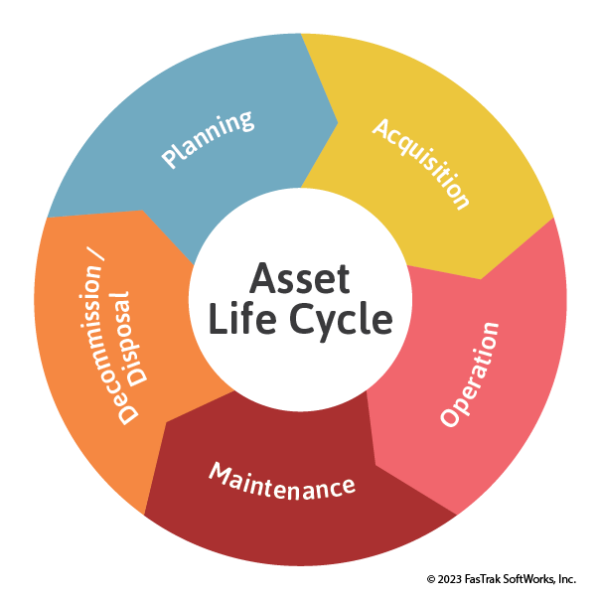

The Asset Life Cycle

Traditional asset management covers the entire asset lifecycle, from cradle to grave. While it can be defined in different ways, it typically consists of the following stages:

- Planning: Recognizing the need for an asset and defining its requirements

- Acquisition: Procuring, installing, setting up, testing, and inspecting the asset. This stage may also include activities such as tracking it in a computerized maintenance management system (CMMS).

- Operation: Using the asset for its intended purpose

- Maintenance: Performed alongside operation to keep the asset running through routine maintenance and repairs

- Decommission/Disposal: discarding or repurposing the asset prior to its replacement

Many of these stages involve teams such as operations, engineering, procurement, and finance. However, maintenance plays a critical role during the operational phase by ensuring that assets continue to perform as expected.

From the perspective of the maintenance team, asset management focuses on preserving asset condition, reducing unplanned downtime, and supporting long-term performance through proactive and reactive maintenance strategies.

Download: Types of Maintenance Infographic

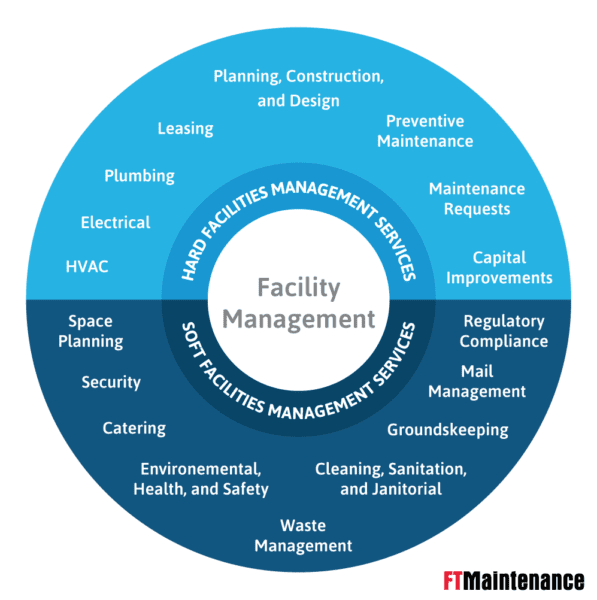

Asset Management vs. Maintenance Management

Though they are commonly used interchangeably, asset management and maintenance management refer to distinct but closely related functions.

Asset management is a broad discipline that focuses on maximizing the value an asset provides throughout its entire lifecycle. It includes activities like evaluating vendors, managing acquisition costs, preparing facilities for installation, training operators, and eventually reclaiming value through resale or disposal. The goal is to extract the greatest total value from each asset.

Maintenance management, on the other hand, deals specifically with coordinating the resources, schedules, and activities required to keep assets in working condition. It includes tasks such as managing spare parts, assigning labor, tracking work orders, and analyzing maintenance costs. While maintenance management supports the goals of asset management, it represents just one piece of the overall asset lifecycle strategy.

Key Elements of Asset Management in Maintenance Operations

Effective asset management within maintenance operations involves several elements that ensure assets are properly identified, tracked, maintained, and optimized. To better understand how maintenance teams manage assets, it helps to break down asset management into more specific categories:

Identification

Maintenance teams must know exactly what assets they are responsible for maintaining. While this may sound like common sense, it can be challenging in practice. A single organization might operate multiple facilities – whether in a single location or across the world – each containing hundreds to hundreds of thousands of assets including equipment and inventory.

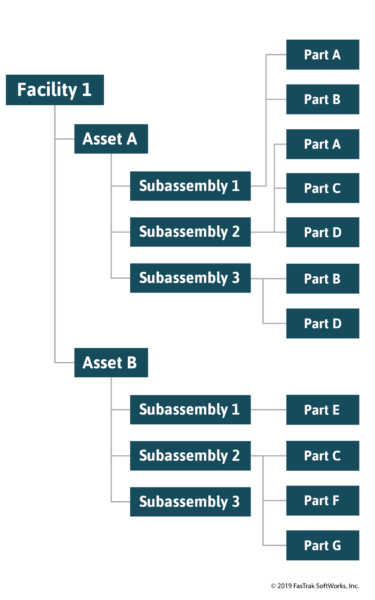

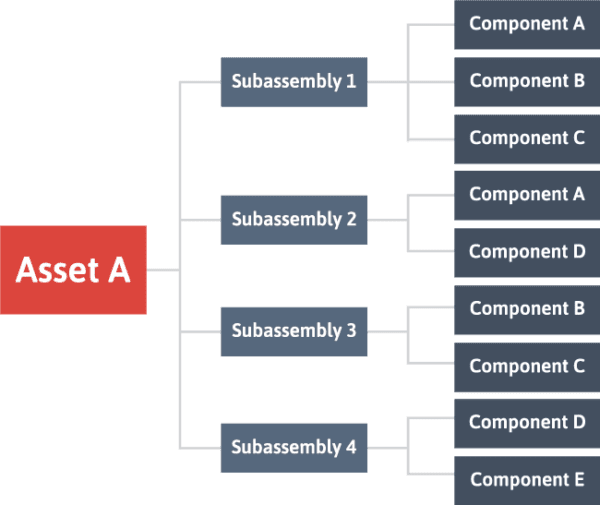

Further, some assets function as one. For example, a production line is a single, integrated system composed of multiple assets working together. Each individual asset is made up of several subassemblies, which can be further broken down into individual parts.

Given this complexity, organizations must have a way to uniquely identify and track assets.

Asset Naming Conventions

Organizations use an asset naming convention to develop consistent, intuitive naming structures that uniquely identify assets and improve recognition, communication, and tracking. Clear naming makes it easier for technicians to locate asset records in asset tracking systems.

Asset Tags

After naming their assets, organizations often create physical labels – typically in the form of barcodes or QR codes – that encode identifying information. These asset tags can be scanned by asset tracking software to read or retrieve information about the asset.

Learn more about barcode systems and their role in maintenance management.

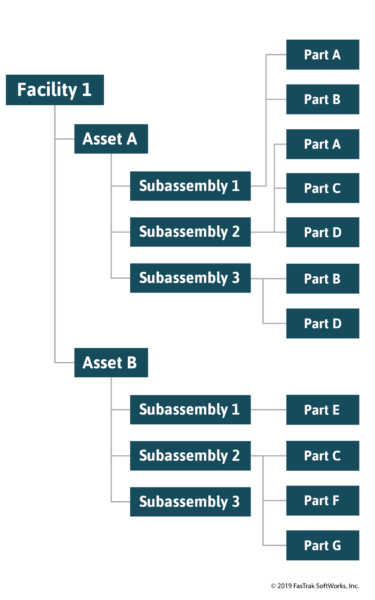

Asset Hierarchies

Asset hierarchies represent how your assets relate to one another using parent-child relationships. It allows maintenance teams to understand an asset’s role within the organization and visualize how assets work together. For example, a facility may contain a production line (parent), which includes a conveyor (child), which in turn includes a motor (grandchild). Depending on the tools used to build them, asset hierarchies can be in the form of a nested list or visual tree structure, helping teams drill down from higher-level systems to individual components.

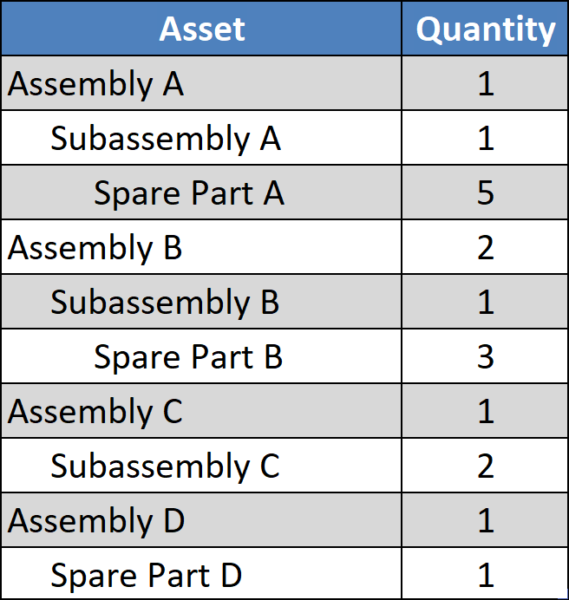

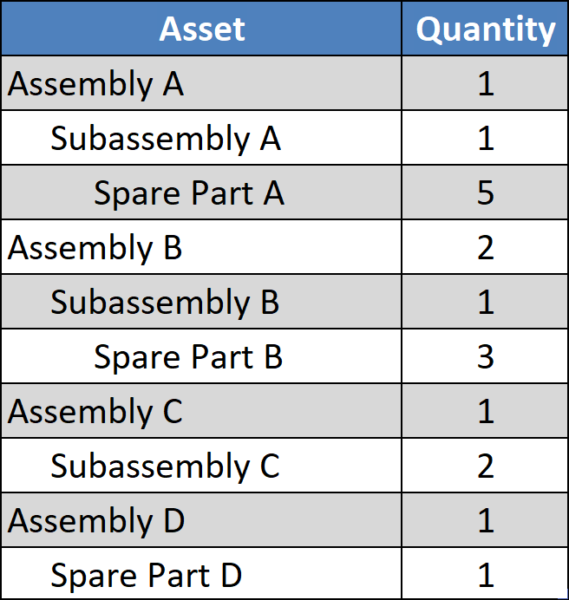

Bills of Materials

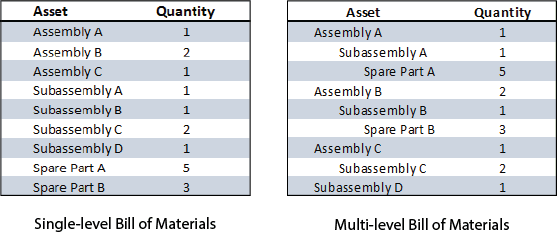

A bill of materials (BOM) is a structured list of parts – along with their respective quantities – used to maintain or repair an asset. It serves as a central point of reference for identifying which components the maintenance team can reasonably expect to repair or replace. BOMs also help organizations anticipate spare part demand, leading to more efficient procurement and inventory management.

Asset Tracking Software

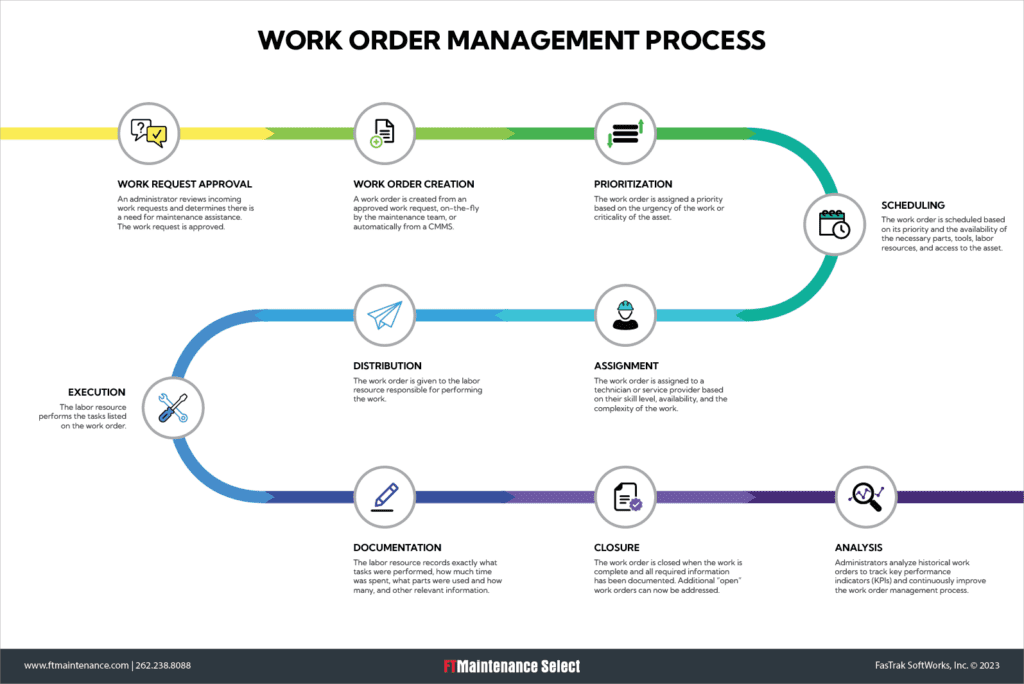

Many organizations utilize asset management software, such as a CMMS, to track assets. These systems typically require a unique number that identifies the record, allowing users to easily identify, navigate to, and select assets.

Asset Location Tracking

It’s not enough to know what assets you have – you must also know where your assets are located. Organizations that manage mobile equipment (like vehicles), movable assets within facilities, or fixed assets across multiple sites need reliable ways to track asset locations.

In many cases, this is as simple as recording the asset’s physical location in a CMMS, spreadsheet, or paper log. For more advanced tracking, technologies like graphic information system (GIS) mapping and global positioning system (GPS) tracking help maintenance teams visualize asset locations and plan work with location in mind.

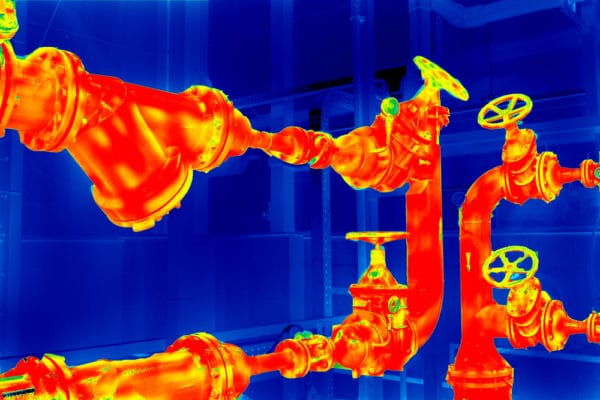

Monitoring Asset Condition

Understanding the condition of an asset is necessary for making decisions such as when to repair or retire equipment. Condition data can be collected in several ways. The most common method is inspection-based preventive maintenance, where technicians visually assess equipment on a regular schedule. More advanced strategies involve continuous condition monitoring using specialized equipment sensors or SCADA systems, which track metrics such as vibration, temperature, or pressure in real time.

Condition monitoring also enables advanced maintenance strategies such as condition-based maintenance (CbM) and predictive maintenance (PdM), which trigger maintenance when specific thresholds are met or forecasted. Additionally, maintenance teams may receive insight into asset health from maintenance requests submitted by machine operators, increasing visibility of emerging issues outside of routine monitoring.

Understanding Asset Design and Specifications

Understanding an asset’s design and specifications is essential for effective maintenance. An asset’s design influences its maintainability, or how easy or difficult it is to service. Knowing an asset’s design can affect how maintenance is planned or performed.

Specifications define the acceptable operating parameters for an asset – such as speed, temperature, or pressure – to help set performance expectations. For maintenance teams, this information is used to guide appropriate maintenance strategies, troubleshoot breakdowns, and ensure part compatibility so that the asset continues to operate within its intended range.

Specifications also help maintenance teams decide which replacement parts are compatible, which materials should be used, and what tolerances are acceptable during repair. When failures occur, comparing equipment’s actual performance to spec can help diagnose issues and be used to determine whether assets can be restored or need to be replaced.

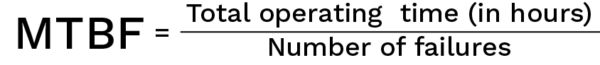

Maintenance Planning and Execution

After documenting basic information about their assets, organizations can develop structured maintenance plans. These plans often include a mix of maintenance strategies tailored to each asset’s condition, criticality, usage, and risk of failure.

For example, corrective maintenance may be appropriate for non-critical assets that are inexpensive to repair or used infrequently. Preventive maintenance is used heavily on high-value or high-risk assets to minimize unplanned downtime. More advanced strategies may incorporate condition monitoring to trigger maintenance based on real-time performance data.

Often times, multiple maintenance strategies are applied to a single asset based on the many ways in which it can fail. Choosing the right combination ensures maximum reliability without unnecessary maintenance.

Cost Control

Asset management aims to maintain equipment at the lowest possible cost. However, as assets age, they require more frequent repairs and become increasingly costly to maintain. To keep costs under control, maintenance teams must strategically apply cost-effective maintenance strategies that extend asset life and reduce the total cost of ownership.

Maintenance costs are influenced not only by the chosen strategy, but also the specific tasks performed, the parts used, and the labor required. This demands careful coordination of inventory, workforce management, and when necessary, external service providers.

Over time, every asset reaches a point where maintenance becomes more costly than replacement. By analyzing maintenance data, maintenance managers can make informed decisions about whether to continue repairing equipment or invest in more efficient replacements.

Learn more about making repair vs. replace decisions.

Safety and Regulatory Compliance

In addition to improving performance, asset management also supports safety and regulatory compliance. Poorly maintained assets pose serious safety risks to operators and technicians, and may result in violations of workplace safety regulations or industry-specific standards. Proactive and consistent maintenance reduces the likelihood of accidents, injuries, and unexpected failures.

Asset management software also helps enforce compliance by documenting that specific tasks – such as safety inspections, calibration, or part replacements – have been completed on time, in full, and according to standards. These records can be provided during audits to demonstrate compliance and protect the organization from fines, penalties, and other liabilities

Many maintenance standards incorporate asset management best practices for improving performance, extending asset life, and reducing unplanned downtime. Following these guidelines ensures that compliance and safety become common practices within your maintenance operations.

Tracking Performance

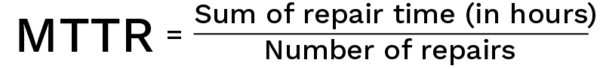

To determine whether their asset management efforts are delivering results, maintenance teams must track asset management key performance indicators (KPIs) related to equipment health and reliability. Monitoring metrics such as Mean Time to Repair (MTTR), Mean Time Between Failures (MTBF), and Overall Equipment Effectiveness (OEE) provide visibility into how well assets are performing and whether maintenance strategies are working.

CMMS platforms automatically capture the data used in these calculations and provide reports and dashboards that help you visualize your performance over time. These tools help teams identify problem areas, adjust maintenance plans, and continuously improve their asset management practices.

Manage Your Assets with FTMaintenance Select

Asset management is all about getting the most value from your equipment and assets. For maintenance teams, that means optimizing equipment performance while minimizing cost. Effectively managing assets across an entire organization is a big responsibility, but is made easier with the proper tools in place.

FTMaintenance Select is an asset management platform that allows maintenance teams to easily track, manage, and document maintenance performed on fixed assets, equipment, and facilities. With all asset data centralized in one platform, your team can plan more effectively, reduce downtime, and make smarter maintenance decisions. Request a demo today to see how FTMaintenance Select supports your asset management goals.

Recent Comments