To minimize costly downtime, maintenance teams first treat the symptoms of failure in order to return assets to service quickly. While corrective actions may provide relief, they do not address the failure’s true underlying cause. Root cause analysis (RCA) allows organizations to uncover the origin of equipment failures.

What is Root Cause Analysis?

First, let’s address what is meant by a “root cause”. According to the American Society of Quality (ASQ), a root cause is “the core issue […] that sets in motion the entire cause-and-effect reaction that ultimately leads to the problem(s).” It is the main contributor to an asset failure.

Root cause analysis (RCA) is a systematic process for investigating why a specific incident occurred. Using various approaches, tools, and problem-solving techniques, RCA provides a structured way for organizations to fully understand the circumstances surrounding a failure, identify its root cause(s), and determine an approach for responding to and resolving it.

Compared to troubleshooting, which is a process of trial and error, root cause analysis is a formal, in-depth examination of physical, human, or organizational factors that may contribute to equipment failure.

Importance of Root Cause Analysis

Without determining a failure’s root cause(s), you cannot make the changes necessary to prevent it from recurring. You may simply perform corrective maintenance (CM) and consider the problem solved, only for it to happen again. Addressing the “symptoms” of a problem does not solve the root cause, even though a repair may provide temporary relief.

RCA provides guidance for determining why an incident occurred by exploring what happened and how. Based on your investigation, you can implement controls that prevent the incident, or similar incidents, from recurring. As a result, you organization can avoid unnecessary costs due to downtime, audits and regulations, and subpar asset reliability.

When to Perform Root Cause Analysis

What failure events prompt the need for a root cause analysis is ultimately your choice. However, you don’t need to perform RCA for every single failure, nor should you. Many problems are relatively minor, happen infrequently, or you already know their cause (e.g., a part that fails because it has reached the end of its useful life). The best candidates for root cause analysis are:

- Chronic failures that occur regularly and are not solved by fixing symptoms

- Failures in mission-critical assets for which there is no backup or way to mitigate the effects of failure

- Critical failures that have a significant negative impact on the organization or endanger the health and safety of employees

Also consider that proper root cause analysis requires a significant amount of time, manpower, money, and knowledge to complete. Important information is often missing because it is generally not possible (or practical) to monitor everything needed for RCA. When data is available, it can be onerous to construct a timeline of events and identify a root cause, of which there may be more than one. Further, it is simply not practical or cost effective to thoroughly investigate every failure, no matter how small.

Root Cause Analysis Tools and Techniques

Root cause analysis uses various approaches, tools, and techniques to determine the causes of asset failure. The International Organization for Standards (ISO) and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) list multiple analysis tools and techniques in their risk management standard, ISO.IEC 31010:2019. For your convenience, the most common RCA tools are described below.

Keep in mind that no RCA tool or technique is foolproof – each has its own pros and cons. Also, some methods may be more applicable to certain industries or types of problems. Your organization should develop its own approach to root cause analysis.

The Five Whys Method

“The Five Whys” (5 Whys) is a popular problem-solving technique that originates from Sakichi Toyoda, founder of Toyota Industries, in the 1930s.It is considered one of the easiest RCA tools. The main idea behind the Five Whys method is “by repeating why five times, the nature of the problem as well as its solution becomes clear.” However, five whys is simply a guideline – some problems can be solved using more or less why questions.

Below is an example of the 5 Whys method:

Problem: A blower motor is vibrating excessively

- Why? The motor bearing failed.

- Why? The motor bearing overheated.

- Why? The bearing was improperly lubricated.

- Why? The amount of lube being injected was less than the recommend amount.

- Why? The grease inlet was clogged.

Possible Solution: Schedule a preventive maintenance task to clean the grease inlet.

Five Whys can also be applied to your maintenance process:

Problem: A preventive maintenance (PM) work order is overdue

- Why? The activity took longer than expected.

- Why? The required parts were not in stock.

- Why? Parts were not purchased on time.

- Why? Demand for the parts was unknown.

- Why? Parts usage was not properly documented in the CMMS.

Possible Solution: Configure the CMMS to require users to enter quantities of used parts.

Fishbone Diagram Analysis (Ishikawa diagram)

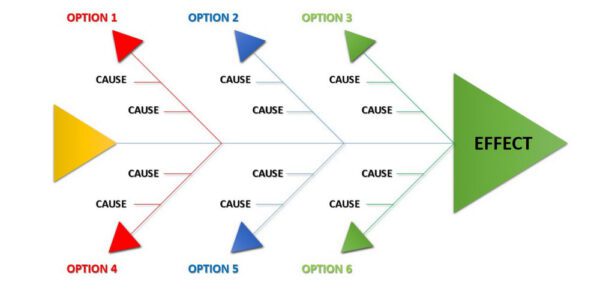

An Ishikawa diagram, better known as the fishbone diagram due to its resemblance of a fish skeleton, helps organizations identify many possible causes of a problem. The problem or adverse effect is displayed at the “head” while causes categories are shown as “bones” feeding into the spine. Commonly used categories include:

- Man (People)

- Machine / Equipment

- Method

- Measurement

- Material

- Environment

Each possible cause makes up smaller “bones” that branch off of their applicable category. After all possible causes are identified, analyze each cause (possibly by using the Five Whys Method) and brainstorm solutions.

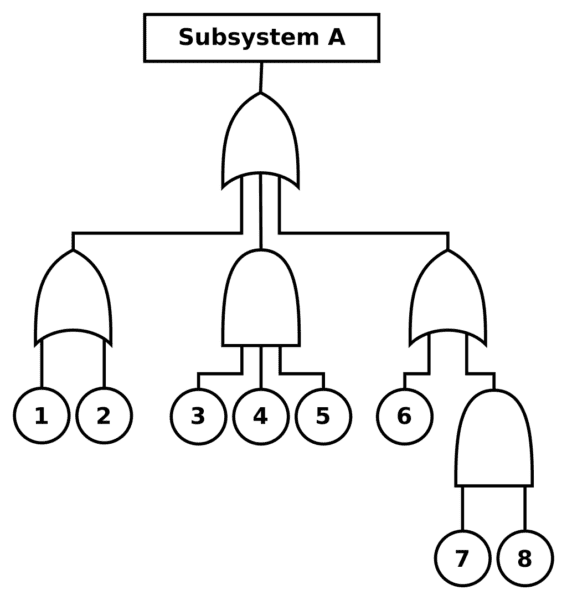

Fault Tree Analysis

Image derived from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fault_tree_analysis

Fault tree analysis (FTA) is a top-down approach to problem solving that uses a graphical tree diagram to map the relationships between a fault and its related events using Boolean logic. The undesirable event is shown at the top of the diagram, and lower level events are connected through “logic gates” representing AND or OR operators.

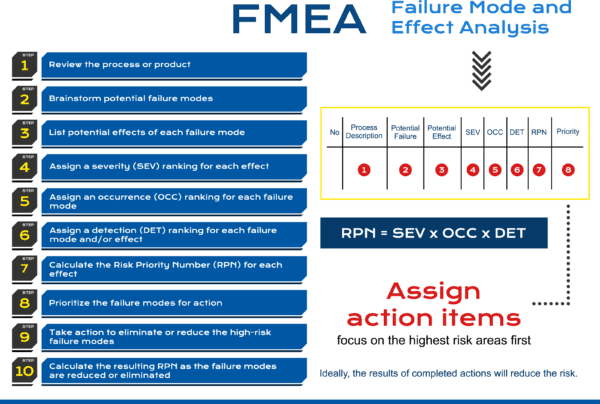

Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA)

Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) is one of the most complex methods of root cause analysis. At the start of the process, a cross-functional team identifies all the ways in which an asset might fail, known as “failure modes”. Typical types of failure modes include:

- Premature operation

- Failure to operate at the prescribed time

- Failure to cease operations at the prescribed time

- Failure during operation

- Degraded or excessive operational capability

Next, the team conducts an “effect analysis” to systematically assess the risk each failure modes poses. Risk is quantified by generating a risk priority number (RPN), which represents a failure mode’s severity, probability of occurrence, and likelihood to be detected. Based on the RPN, the organization identifies failure modes that pose the highest risk to the organization and create a plan to prevent them or mitigate their risk. The ASQ provides an example of an FMEA procedure on their website.

Pareto Analysis

Pareto analysis is a decision-making tool that helps organizations identify which failure causes are the most significant. It is based on the Pareto principle, better known as the “80/20 rule”, which states that 80% of failures come from 20% of causes.

Using Pareto analysis, a Pareto chart is created to plot the frequency of causes and their cumulative effects. The Pareto chart is a combination of a bar chart and line chart. The bars represent the frequency of causes, with the most frequent on the left and least frequent on the right. The line chart shows the cumulative sum of each cause’s percentage.

Root Cause Analysis Process

The specific steps taken when performing root cause analysis differ based on the tools and techniques used. In general, the RCA process is as follows:

- Define the problem:

- Clearly and concisely define the problem.

- Collect preliminary data about the failure, including specific symptoms and effects.

- Create a problem statement.

- Collect data: Gather all data relevant to the failure, such as what happened before and after, who interacted with the machine, and important details about the asset.

- Identify causal factors: Create a timeline of events and examine any contributing or related causal factors.

- Identify the root cause:

- Use one or more root cause analysis tools and techniques to identify the root cause.

- Determine the best solution to address the root cause.

- Implement solutions:

- Develop an action plan to address the root cause to prevent it from recurring.

- Monitor and evaluate the solution after implementation.

Root Cause Analysis and CMMS

A computerized maintenance management system (CMMS) is an invaluable tool for performing root cause analysis. It provides a way for maintenance teams to document and track critical asset and maintenance data that can be used when analyzing asset failures.

Work orders track what problems your assets have experienced and what resolved them. Organizations can quickly access important asset information, meter readings, and preventive maintenance schedules to provide context to the events surrounding failures. Some CMMS systems offer failure tracking and analysis through failure cause tracking. Read our series of articles about failure codes for more information.

When a root cause is identified, the CMMS can be used to easily create or modify preventive maintenance schedules, update PM task lists, attach supplementary maintenance documentation, and document new maintenance procedures. Maintenance reports help you monitor and track the results of any new or changed maintenance activities introduced to address the root cause.

Track Equipment Failures with FTMaintenance Select

The maintenance team is a key source of information for teams performing root cause analysis. Organizations must have a solution in place to store critical data about assets, work orders, and maintenance schedules.

FTMaintenance Select provides a centralized platform for documenting, managing, and tracking maintenance activities and creating a repository of information about asset maintenance and performance. Request a demo today to learn more about how to create a proactive maintenance plan and prevent critical failures with FTMaintenance Select.

Recent Comments